Camden's Britannia

the farthest county of the Silures seems to be that we call Glamorganshire; the Britons Morganwg, Gwlad Morgan, and Gwlad Vorganwg, which signifies the county of Morganwg; and was so called (as most imagine) from Morgan a prince; or (as others suppose) from an abbey of that name. But if I should deduce it from the British mor, which signifies the sea, I know not for certain whether I should deviate from the truth. However, I have observed that maritime town of Armorica, we call now Morlais, to have been called by Ptolemy and the ancient Gauls Vorganium, or Morganium (for the letters m and v are often counterchanged in this language:) and whence shall we suppose it thus denominated but from the sea? And this our Morganwg is also altogether maritime; being a long narrow country, wholly washed on the South side by the Severn Sea. As for the inner part of it, it is bordered on the East with Monmouthshire, on the North with Brecknock, and on the West with Carmarthenshire.

on the North it is very rugged with mountains, which inclining towards the South, become by degrees more tillable; at the roots whereof we have a spacious vale or plain open to the South sun; a situation which Cato preferred to all others, and for which Pliny does so much commend Italy. For this part of the country is exceeding pleasant, both in regard of the fertility of the soil, and the number of towns and villages.

In the reign of William Rufus, Jestin ap Gwrgant Lord of this country, having revolted from his natural prince Rhys ap Tewdwr and being too weak to maintain his rebellion, very unadvisedly, which he too late repented, called to his assistance (by mediation of Enion ap Kadivor a nobleman, who had married his daughter) Robert Fitz-Haimon, a Norman, son of Haimon Dentatus Earl of de Corbeil, who forthwith levied an army of choice soldiers, and taking to his assistance twelve knights as adventurers in this enterprise, first gave Rhys battle, and slew him; and afterwards being allured with the fertility of the country, which he had before conceived sure hopes to be Lord of, turning his forces against Jestin himself, for that he had not kept his articles with Enion, he soon deprived him of the inheritance of his ancestors, and divided the country amongst his partners. The barren mountains he granted to Enion; but the fertile plains he divided amongst these twelve associates, (whom he had called peers) and himself; on that condition, that they should hold their land in fee and vassalage of him as their chief Lord, to assist each other in common; and that each of them should defend his station in his castle of Cardiff, and attend him in his court at the administration of justice. It may not perhaps be foreign to our purpose, if we add their names out of a book written on this subject, either by Sir Edward Stradling, or Sir Edward Maunsel (for 'tis ascribed to both of them) both being very well skilled in genealogy and antiquities.

William of London, or de Londres.

Richard Granvil.

pain Turbervil.

Oliver St. John.

Robert de St. Quintin.

Roger Bekeroul.

William Easterling, (so called, for that he was descended from Germany) whose posterity were called Stradlings.

Gilbert Humfraville.

Richard Siward.

John Fleming.

Peter Soore.

Reginald Sully.

the river gliding from the mountains, makes Rhymney the eastern limit of this county, whereby it is divided from Monmouthshire; and in the British, remny signifies to divide. In a moorish bottom, not far from this river, where it runs through places scarce passable among the hills, are seen the ruinous walls of Caerphilly Castle, which has been of that vast magnitude, and such an admirable structure, that most affirm it to have been a Roman garrison; nor shall I deny it, though I cannot yet discover by what name they called it. However, it should seem to have been re-edified, in regard it has a chapel built after the Christian manner, as I was informed by the learned and judicious Mr. J. Sanford, who took an accurate survey of it. It was once the possession of the Clares Earls of Gloucester; but we find no mention of it in our annals, till the reign of Edward the Second. For at that time the Spensers having by underhand practices set the King and Queen and the barons at difference, we read that Hugolin Spenser was a long time besieged in this castle, but without success. Upon this river also (but the place is uncertain) Nennius informs us that Faustus a pious godly son of Vortigern a most wicked father, erected a stately edifice, where, with other devout men, he daily prayed unto God, that he would not punish him for the sins of his father, who committing most abominable incest, had begotten him on his own daughter; and that his father might at last seriously repent, and the country be freed from the Saxon war.

a little lower, Ptolemy places the mouth of Rhatostabius, or Rhatostibius, a maimed word, for the British Traeth Tav, which signifies the sandy firth of the river Taff. For there the river Taff gliding from the mountains falls into the sea at Llandaff, that is, the church on the river Taff, a small place seated in a bottom, but dignified with a bishop's see (in the diocese whereof are 154 parishes) and adorned with a cathedral consecrated to St. Teiliau bishop thereof. Which church was then erected by the two Gallic bishops Germanus and Lupus, when they had suppressed the Pelagian heresy that prevailed so much in Britain: and Dubricius a most devout man they first preferred to the bishopric, to whom Meuric a British prince granted all the lands between Taff and Ely. From hence Taff continues its course to Cardiff, in British Caer Dydh corruptly I suppose for Caer Dyv, a neat town considering the country, and a commodius haven; fortified with walls and a castle by the conqueror Fitz-Haimon, who made it both the seat of war, and a court of justice. Where, besides a standing army of choice soldiers, the twelve knights or peers were obliged each of them to defend their several stations. Notwithstanding which, a few years after, one Ivor Bach, a Briton who dwelt in the mountains, a man of small stature, but of resolute courage, marched hither with a band of soldiers privately by night, and seized the castle, carrying away William Earl of Gloucester, Fitz-Haimon's grandson by the daughter, together with his wife and son, whom he detained prisoners till he had received satisfaction for all injuries. But how Robert Curthose, eldest son of William the Conqueror (a man in martial prowess, but too adventurous and fool-hardy) was deprived by his younger brothers of all hopes of succession to the crown; and bereft of both his eyes, lived in this castle till he became an old man; may be seen in our English historians. Whereby we may also learn, that to be born of the blood-royal, does not ensure us of either liberty or safety.

scarce three miles from the mouth of the river Taff, in the very winding of the shore, there are two small, but very pleasant islands, divided from each other, and also from the mainland, by a narrow firth. The hithermost is called Sully, from a town opposite to it; to which Robert de Sully (whose share it was in the division) is thought to have given name; though we might as well suppose he took his name from it. The furthermost is called Barry, from St. Baruch who lies buried there; who as he gave name to the place, so the place afterwards gave surname to its proprietors. For that noble family of Viscount Barry in Ireland, is thence denominated. In a maritime rock of this island, saith Giraldus, there is a narrow chink or chest, to which if you put your ear, you shall perceive such a noise as if smiths were at work there. For sometimes you hear the blowing of the bellows, at other times the strokes of the hammers; also the grinding of tools, the hissing noise of steel-gads, of fire burning in furnaces, &c. These sounds I should suppose might be occasioned by the repercussion of the sea-waters into these chinks, but that they are continued at low ebb when there's no water at all, as well as at the full tide. Nor was that place unlike to this which Clemens Alexandrinus mentions in the seventh book of his Stromata. Historians inform us, that in the Isle of Britain there is a certain cave at the root of a mountain, and at the top of it a cleft. Now when the wind blows into the cave, and is reverberated therein, they hear at the chink the sound of several cymbals; for the wind being driven back makes much the greater noise.

beyond these islands the shore is continued directly westward, receiving only one river; upon which (a little more within the land) lies Cowbridge, called by the Britons, from the stone bridge, Y Bont Vaen; a market town, and the second of those three which the conqueror Fitz-Haimon reserved for himself. In regard Antoninus places the city Bovium (which is also corruptly called Bomium) in this tract, and at this distance from Isca, I flattered myself once with the conjecture that this must be Bovium. But seeing that at three miles distance from this town we find Boverton, which agrees exactly with Bovium, I could not without an injury to truth, seek for Bovium elsewhere. Nor is it a new thing, that places should receive their names from oxen, as we find by the Thracian Bosphorus; the Bovianum of the Samnites; and Bauli in Italy, so called quasi Boalia, if we may credit Symachus. But let this one argument serve for all: fifteen miles from Bovium, Antoninus using also a Latin name hath placed Nidum, which though our antiquaries have a long time searched for in vain, yet at the same distance we find Neath [in British Nedh] a town of considerable note, retaining still its ancient name almost entire. Moreover, we may observe here, at Llantwit or St. Iltut's, a village adjoining, the foundations of many buildings; and formerly it had several streets. Not far from this Boverton, almost in the very creek or winding of the shore, stands St. Donat's Castle, the habitation of the ancient and noble family of the Stradlings; near which there were dug up lately several ancient Roman coins, but especially of the 30 tyrants,<339> and some of Aemilianus and Marius, which are very scarce. A little above this the river Ogmore Ogmore river. Falls into the sea, which glides from the mountains by Coity Castle, the seat formerly of the Turbervilles, afterwards of the Gamages, and now (in right of his lady) of Sir Robert Sidney Viscount L'Isle; and also by Ogmore Castle, which devolved from the family of the Londons to the Duchy of Lancaster.

There is a remarkable spring within a few miles of this place (as the learned Sir John Stradling told me by letter) at a place called Newton, a small village on the West side of the river Ogmore, in a sandy plain about a hundred paces from the Severn shore. The water of it is not the clearest, but pure enough and fit for use: it never runs over; insomuch, that such as would make use of it must go down some steps. At full sea, in summer time, you can scarce take up any water in a dish; but immediately when it ebbs, you may raise what quantity you please. The same inconstancy remains also in the winter; but is not so apparent by reason of the adventitious water, as well from frequent showers as subterraneous passages. This, several of the inhabitants, who were persons of credit, had assured me of. However being somewhat suspicious of common report, as finding it often erroneous, I lately made one or two journeys to this sacred spring, for I had then some thoughts of communicating this to you. Being come thither, and staying about the third part of an hour (whilst the Severn flowed, and none came to take up water) I observed that it sunk about three inches. Having left it, and returning not long after, I found the water risen above a foot. The diameter of the well may be about six foot. Concerning which my muse dictates these few lines:

te Nova-Villa fremens, odioso murmure Nympha

inclamat Sabrina: soloque inimica propinquo,

evomit infestas ructu violenter arenas.

damna pari sentit vicinia sorte: sed illa

fonticulum causata tuum. Quem virgo, legendo

litus ad amplexus vocitat: latet ille vocatus

antro, & luctatur contra. Namque aestus utrique est.

continuo motu refluus, tamen ordine dispar.

nympha fluit propius: fons defluit. Illa recedit.

iste redit. Sic livor inest & pugna perennis.

thee, Newton, Severn's noisy Nymph pursues,

while unrestrained th' impetuous torrent flows.

her conquering surges waste thy hated land,

and neighbouring fields are burdened with the sand.

but all the fault is on thy fountain laid,

thy fountain courted by the amorous maid.

him, as she passeth on, with eager noise

she calls, in vain she calls, to mutual joys.

he flies as fast, and scorns the proffered love,

(for both with tides and both with different move.)

the Nymph advanceth, straight the fountain's gone,

the Nymph retreats, and he returns as soon.

thus eager love still boils the restless stream,

and thus the cruel spring still scorns the virgin's flame.

Polybius takes notice of such a fountain at Cadiz, and gives us this reason for it; viz. that the air being deprived of its usual vent, returns inwards; by which means the veins of the spring being stopped, the water is kept back: and so on the other hand, the water leaving the shore, those veins or natural aqueducts are freed from all obstruction, so that the water springs plentifully.

from hence coasting along the shore, you come to Kenfig, the castle heretofore of Fitz-Haimon; and Margam once a monastery, founded by William Earl of Gloucester, and now the seat of the noble family of the Mansels, knights. Not far from Margam, on the top of a hill called Mynydd Margam, there is a pillar of exceeding hard stone, erected for a sepulchral monument, of about four foot in height, and one in breadth; with an inscription, which whoever happens to read, the ignorant common people of that neighbourhood promise he shall die soon after. Let the reader therefore take heed what he does; for if he reads it, he shall certainly die.

Illustration: Mynydd Margam Pillar

Which reads

BODOCUS HIC JACIT, FILIUS CATOTIS,

IRNI PRONEPOS, ETERNALI VE DOMAU.

the last words I read, aeternali in domo; for in that age sepulchres were called aeternales domus. <340>

Betwixt Margam and Kenfig also, by the way side, lies a stone about four foot long, with this inscription:

![]()

Illustration: Stone between Margam and Kenfig

which the Welsh (as the right reverend the Bishop of Llandaff, who sent me this copy of it, informs me) by adding and changing some letters, do thus read and interpret PVMP. BVS CAR A'N TOPIVS. i.e. "The five fingers of our friend or kinsman killed us." They suppose it to have been the grave of Prince Morgan, from whom the county received its name, who they say was killed eight hundred years before the birth of our saviour; but antiquaries know, these letters are of much later date.

from Margam the shore leads Northeastward, by Aberavon, a small market town, at the mouth of the river Avon (whence it takes its name) to Neath, a river infamous for its quicksands; upon which stands an ancient town of the same name, in Antonine's itinerary called Nidum. Which, when Fitz-Haimon subdued this country, fell in the division to Richard Granville; who having built there a monastery under the town, and consecrated his dividend to God and the monks, returned to a very plentiful estate he had in England.

all the country from Neath to the river Loughor, which is the western limit of this country, is called by us Gower, by the Britons Gwyr, and by Nennius Guhir: where (as he tells us) the sons of Keian a Scot seated themselves, until they were driven out by Kynedhav a British prince. In the reign of King Henry the First, Henry Earl of Warwick subdued this country of Gower; which afterwards by compact betwixt Thomas Earl of Warwick and King Henry the Second, devolved to the crown. But King John bestowed it on William de Breos, to be held by service of one knight, for all service. And his heirs successively held it, till the time of Edward the Second. For at that time William de Breos having sold it to several persons; that he might ingratiate himself with the King, deluded all others, and put Hugh Spenser in possession of it. And that, amongst several others, was the cause why the nobles became so exasperated against the Spensers, and so unadvisedly quitted their allegiance to the King. It is now divided into East and West Gowerland. In East Gowerland the most noted town is Swansea, so called by the English from porpoises or sea-hogs; and by the Britons Abertawi (from the river Tawi, which runs by it) fortified by Henry Earl of Warwick. But a more ancient place than this, is that at the river Loughor which Antoninus calls Leucarum, and is at this day (retaining its ancient name) called Loughor [in British Casllwchwr] where, about the death of King Henry the First, Howel ap Mredydh with a band of mountaneers, surprised and slew several Englishmen of quality. Beneath this lies West Gower, which (the sea making creeks on each side it) is become a peninsula; a place more noted for the corn it affords, than towns. And celebrated heretofore for St. Kynedhav, who led here a solitary life; of whom such as desire a further account, may consult our Capgrave, who has sufficiently extolled his miracles.

from the very first conquest of this country, the Clares and Spensers Earls of Gloucester (who were lineally descended from Fitz-Haimon) were lords of it. Afterwards the Beauchamps, and one or two of the Nevilles; and by a daughter of Neville (descended also from the Spensers ) it came to Richard the Third King of England, who being slain, it devolved to King Henry the Seventh, who granted it to his uncle Gasper Duke of Bedford. He dying without issue, the King resumed it into his own hands, and left it to his son Henry the Eighth; whose son Edward the Sixth sold most part of it to William Herbert, whom he had created Earl of Pembroke, and Baron of Cardiff.

of the offspring of the twelve knights before-mentioned, there remain now only in this county the Stradlings, a family very eminent for their many noble ancestors; with the Turbervilles, and some of the Flemings, whereof the chiefest dwells at Flemingstone, called now corruptly from them Flemston. But in England there remain my Lord St. John of Bletso, the Granvilles in Devonshire, and the Siwards (as I am informed) in Somersetshire. The issue male of all the rest is long since extinct, and their lands by daughters passed over to other families.

Parishes in this county 118.

additions to Glamorganshire.

in our entrance upon this county, we are presented with Caerphilly Castle, probably the noblest ruins or ancient architecture now remaining in Britain. For in the judgment of some curious persons, who have seen and compared it with the most noted castles of England, it exceeds all in bigness, except that of Windsor. That place which Mr. Sanford called a chapel, was probably the same with that which the neighbouring inhabitants call the hall. It is a stately room about 70 foot in length, 34 in breadth, and 17 in height. On the South side we ascend to it by a direct stair-case, about eight foot wide; the roof whereof is vaulted and supported with twenty arches, which are still gradually higher as you ascend. The entry out of this stair-case, is not into the middle, but somewhat nearer to the West end of the room; and opposite to it on the North side, there is a chimney about ten foot wide. On the same side there are four stately windows (if so we may suppose them) two on each side the chimney, of the fashion of church-windows; but that they are continued down to the very floor, and reach up higher than the height of this room is supposed to have been; so that the room above this chapel [or hall] had some part of the benefit of them. The sides of these windows are adorned with certain three-leaved knobs or husks, having a fruit or small round ball in the midst. On the walls on each side the room, are seven triangular pillars, like the shafts of candlesticks, placed at equal distance. From the floor to the bottom of these pillars, may be about twelve foot and a half; and their height or length seemed above four foot. Each of these pillars is supported with three busts, or heads and breasts, which vary alternately. For whereas the first (for example) is supported with the head and breast of an ancient bearded man and two young faces on each side, all with disheveled hair; the next shows the face and breasts of a woman with two lesser faces also on each side, the middlemost or biggest having a cloth close tied under the chin, and about the forehead; the lesser two having also forehead-cloths, but none under the chin, all with braided locks. (See the figures in Curiosities of Wales, below, No. 3 and 4.) The use of these pillars seems to have been for supporting the beams; but there are also on the South side six grooves or channels in the wall at equal distance, which are about nine inches wide, and eight or nine foot high: four whereof are continued from the tops of the pillars; but the two middlemost are about the middle space between the pillars, and come down lower than the rest, having neat stones jutting out at the bottom, as if intended to support something placed in the hollow grooves. On the North side, near the East end, there's a door about eight foot high; which leads into a spacious green about seventy yards long and forty broad. At the East end there are two low-arched doors, within a yard of each other; and there was a third near the South side, but much larger; and another opposite to that on the West end. The reason why I have been thus particular, is, that such as have been curious in observing ancient buildings, might the better discern whether this room was once a chapel or hall, &c. And also in some measure judge of the antiquity of the place; which, as far as I could hitherto be informed, is beyond the reach of history.

that this castle was originally built by the Romans, seems indeed highly probable, when we consider its largeness and magnificence. Though at the same time we must acknowledge, that we have no other reason to conclude it Roman, but the stateliness of its structure. For whereas most or all Roman cities and forts of note, afford (in the revolution at least of fifty or sixty years) either Roman inscriptions, statues, bricks, coins, arms, or other utensils, I could not find, upon diligent enquiry, that any of their monuments were ever discovered here. I have indeed two coins found at this castle; one of silver, which I received amongst many greater favours from the right worshipful Sir John Aubrey of Llantrithyd, baronet; and the other of brass, which I purchased at Caerphilly of the person that found it in the castle. (See the table of Welsh Curiosities, no. 25 & 26.) Neither of these are either Roman or English, and therefore probably Welsh. That of silver is as broad, but thinner than a sixpence, and exhibits on one side the image of our saviour with this inscription,

![]()

and on the reverse 2 persons, I suppose saints, with these letters

![]()

the meaning whereof I dare not pretend to explain; but if any should read it moneta veneti regionis, the money of the country of Gwynedd in North Wales, or else Gwent or Went Land, it might perhaps pass as a conjecture something probable, though I should not much contend for it. The brass coin is like the French pieces of the middle age, and shows on the obverse a prince crowned, in a standing posture, holding a sceptre in his right hand, with this inscription

![]() ave Maria, &c;

ave Maria, &c;

and on the reverse a cross florée with these letters,

![]() ave.

ave.

Taking it for granted that this place was of Roman foundation, I should be apt to conjecture (but that our learned and judicious author has placed Bullaeum mentioned by Ptolemy, in another county) that what we now call Caerphilly, was the Bullaeum Silurum of the Romans. Probably Mr. Camden had no other argument (since he produces none) to conclude that Builth a town in Brecknockshire, was the ancient Bullaeum, but from the affinity of the names; and for that he presumed it seated in the country of the Silures. If so, we may also urge, that the name of Caerphilly comes as near Castrum Bullaei, as Builth. For such as understand the British tongue, will readily allow, that Bullaeum could not well be otherwise expressed in that language, that Caer Vwl, (which must be pronounced Caer vyl) or (as well as some other names of places) from the genitive case, Caer-vyli. That this place was also in the country of the Silures, is not controverted: and further, that it has been a Roman garrison is so likely, from the stately ruins still remaining, that most curious persons who have seen it, take it for granted. Whereas I cannot learn that anything was ever discovered at Builth, that might argue it inhabited by the Romans; much less a place of note in their time, as Bullaeum Silurum must needs have been.

on a mountain called Cefn Gelli-gaer, not far from this Caerphilly, in the way to Marchnad Y Wayn; I observed (as it seemed to me) a remarkable monument, which may perhaps deserve the notice of the curious. It's well known by the name of y Maen Hir, and is a rude stone pillar of a kind of quadrangular form, about 8 foot high; with this inscription to be read downwards:

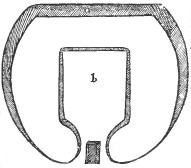

![]()

it stands not erect, but somewhat inclining; whether casually, or that it was so intended, is uncertain. Close at the bottom of it, on that side it inclines, there's a small bank or entrenchment, enclosing some such space as six yards; and in the midst thereof a square area, both which may be better delineated than described.

Illustration: Cefn Gelli-gaer enclosure

I suppose that in the bed or area in the midst, a person has been interred; and that the inscription must be read tefro i ti, or deffro i ti; which is Welsh, and signifies mayst thou awake.

as to the subterraneous noises mentioned by our author: What such soever might be heard in this island in Giraldus's time; 'tis certain (notwithstanding many later writers have upon this authority taken it for granted) that at present there are no such sounds perceived here. A learned and ingenious gentleman of this country, upon this occasion writes thus: I was myself once upon the island, in company with some inquisitive persons; and we sought over it where such noise might be heard. Upon failure, we consulted the neighbours, and I have since asked literate and knowing men who lived near the island; who all owned the tradition, but never knew it made out in fact. Either then that old phenomenon is vanished, or the place is mistaken.

I shall offer upon this occasion what I think may divert you. You know there is in this channel, a noted point of land, between the Nash Point in this county, and that of St. Govan's in Pembrokeshire; called in the maps and charts Worm's Head Point, for that it appears to the sailors, like a worm creeping, with its head erect. From the mainland, it stretches a mile or better into the sea; and at half-flood, the isthmus which joins it to the shore is overflown; so that it becomes then a small island. Toward the head itself, or that part which is farthest out in the sea, there is a small cleft or crevice in the ground, into which if you throw a handful of dust or sand, it will be blown up back again into the air. But if you kneel or lie down, and lay your ears to it, you then hear distinctly the deep noise of a prodigious large bellows. The reason is obvious: for the reciprocal motion of the sea, under the arched and rocky hollow of this headland or promontory, makes an inspiration and expiration of the air, through the cleft, and that alternately; and consequently the noise, as of a pair of bellows in motion. I have been twice there to observe it, and both times in the summer season, and in very calm weather. But I do believe a stormy sea would give not only the forementioned sound, but all the variety of the other noises ascribed to Barry; especially if we a little indulge our fancy, as they that make such comparisons generally do. The same, I doubt not, happens in other places upon the sea-shore, wherever a deep water, and rocky concave, with proper clefts for conveyance,do concur: in Sicily especially, where there are moreover fire and sulphur for the bellows to work upon; and chimneys in those volcanos to carry off the smoke. But now that this Worm's Head should be the intended Isle of Barry, may seem very uncouth. Here I consider, that Burry is the most remarkable river (next that of Swansea) for trade, in all Gower; and its Ostium is close by Worm's Head, so that whoever sails to the NE of Worm's Head, is said to sail for the river of Bury. Worm's Head again is but a late name; but the name of the river Bury is immemorial. Now he that had a mind to be critical might infer, either that Worm's Head was of old called the island of Bury; or at least, that before the name of Worm's Head was in being, the report concerning these noises might run thus: that near Burry, or as you sail into Bury, there is an island, where there is a cleft in the ground, to which if you lay your ear, you'll hear such and such noises. Now Barry for Bury is a very easy mistake, &c.

in the churchyard at Llantwit Major, or Llan Illtud Vawr, on the North side of the church, there are two stones erected, which seem to deserve our notice. The first is close by the church wall, and is of a pyramidal form, about seven foot in height. It is adorned with old British carving, such as may be seen on the pillars of crosses, in several parts of Wales. It is at three several places, at equal distance, encompassed with three circles. From the lowest three circles to the ground, it is ingrailed or indented; but elsewhere adorned with knots. The circumference of it at the three highest circles, is three foot and a half; at the middlemost, above four foot, and the lowest about five. It has on one side, from the top (which seems to have been broken) to the bottom, a notable furrow or canaliculus about four inches broad, and two in depth. Which I therefore noted particularly, because upon perusal of a letter from the very learned and ingenious Dr. James garden of Aberdeen, to Mr. J. Aubrey RSS. I found the doctor had observed that amongst their circular stone-monuments in Scotland, (such as that at Rollright, &c. In England) sometimes a stone or two is found with a cavity on the top of it, capable of a pint or two of liquor; and such a groove or small chink as this I mention, continued downwards from this basin: so that whatever liquor is poured on the top, must run down this way. Whereupon he suggests, that supposing (as Mr. Aubrey does) such circular monument to have been temples of the druids, those stones might serve perhaps for their libamina or liquid sacrifices; but although this stone agrees with those mentioned by Dr. Garden, in having a furrow or cranny on one side; yet in regard of the carving, it differs much from such old monuments; which are generally, if not always, very plain and rude: so that perhaps it never belonged to such a circular monument, but was erected on some other occasion. The other stone is also elaborately carved, and was once the shaft or pedestal of a cross. On the one side it hath an inscription, showing that one Samson set it up, pro anima ejus; and another on the opposite side, signifying also that Samson erected it to St. Iltutus or Illtud; but that one Samuel was the carver. These inscriptions I thought worth the publishing, that the curious might have some light into the form of our letters in the middle ages.

In old inscriptions we often find the letter V where we use O. As in the Mynydd Margam Pillar above, pronepvs for pronepos so that there was no necessity of inventing this character θ (made use of in the former editions) which I presume is such, as was never found in any inscription whatever. In Reinesius Syntag. Inscriptionum p. 700, we find the epitaph of one Boduacus, dug up at Nîmes in France. Whereupon he tells us that the Roman name Betulius was changed by the Gauls into Boduacus. But it may seem equally probable, if not more likely, since we also find Bodvoc here; that it was a Gaulish or British name: and the name of the famous Queen of the Iceni, Boadicea, seems also to share in the same original. Sepulchres are in old inscriptions often called domus aeternae, but aeternalis seems a barbarous word. The last words I read Aeternalis in Domo, for in that age sepulchres were called Aeternales Domus, or rather Aeternae, according to that distich,

docta lyra grata & gestu formosa puella,

hic jacet aeterna Sabis humata domo.<342>

the other inscription mentioned by him (See above, Stone between Margam and Kenfig) is also at this day in the same place, and is called by the common people Bedh Morgan Morganwg, viz. The sepulchre of prince Morgan: which (whatever gave occasion to it) is doubtless an erroneous tradition; it being no other than the tomb-stone of one Pompeius carantopius, as plainly appears by this copy of it I lately transcribed from the stone. As for the word Pumpeius for Pompeius, we have already observed, that in old inscriptions, the letter v is frequently used for o.

There is also another monument, which seemed to me more remarkable than either of these, at a place called Panwen Berthin, in the Parish of Kadokston or Llangadog, about six miles above Neath. It is well known in that part of the county by the name of Maen Dau Lygadyr Ych, and is so called, from two small circular entrenchments, like cock-pits: one of which had lately in the midst of it a rude stone pillar, about three foot in height, with this inscription, to be read downwards.

![]()

which perhaps we must read marci (or perhaps memoriae) Caritini filii Bericii. But what seemed to me most remarkable, were the round areae; having never seen, nor been informed of such places of burial elsewhere. So that on first sight, my conjecture was, that this had happened on occasion of a duel, each party having first prepared his place of interment: and that therefore there being no stone in the centre of the other circle, this inscription must have been the monument of the party slain. It has been lately removed a few paces out of the circle, and is now pitched on end, at a gate in the highway. But that there never was but one stone here, seems highly probable from the name Maen Dau Lygadyr Ych: whereas had there been more, this place, in all likelihood, had still retained the name of Meneu Llydaidyr Ych.

on a mountain called Mynydd Gellionnen in the parish of Llangyfelach, I observed a monument which stood lately in the midst of a small cairn or heap of stones, but is now thrown down and broken in three or four pieces; differing from all I have seen elsewhere. 'Twas a flat stone, about three inches thick, two foot broad at bottom, and about five in height. The top of it is formed as round as a wheel, and thence to the basis it becomes gradually broader. On one side it is carved with some art, but much more labour. The round head is adorned with a kind of flourishing cross, like a garden-knot: below that there is a man's face and hands on each side; and thence almost to the bottom, neat fretwork; beneath which there are two feet, but as rude and ill-proportioned (as are also the face and hands) as some Egyptian hieroglyphic.

not far from hence, within the same parish, is Carn Llechart, A monument that gives denomination to the mountain on which it is erected. 'Tis a circle of rude stones, which are somewhat of a flat form, such as we call llecheu, disorderly pitched in the ground, of about 17 or 18 yards diameter; the highest of which now standing is not above a yard in height. It has but one entry into it, which is about four foot wide: and in the center of the area, it has such a cell or hut, as is seen in several places of Wales, and called cist vaen: one of which is described in Brecknockshire, by the name of St. Iltut's Cell. This at Carn Llechart is about six foot in length, and four wide, and has no top-stone now for a cover; but a very large one lies by, which seems to have slipped off. Y Gist Vaen on a mountain called Mynydd Drumau by Neath, seems to have been also a monument of this kind, but much less; and to differ from it, in that the circle about it was mason-work, as I was informed by a gentleman who had often seen it whilst it stood; for at present there's nothing of it remaining. But these kind of monuments, which some ascribe to the Danes, and others suppose to have been erected by the Britons before the Roman Conquest, we shall have occasion to speak of more fully hereafter. Another monument there is on a mountain called Cefn Bryn, in Gower, which may challenge a place also among such unaccountable antiquities, as are beyond the reach of history; whereof the same worthy person that sent me his conjecture of the subterraneous noise in Barry Island, gives the following account:

as to the stones you mention, they are to be seen upon a jutting at the northwest of Cefn Bryn, the most noted hill in Gower. They are put together by labour enough, but no great art, into a pile; and their fashion and posture is this: there is a vast unwrought stone (probably about twenty ton weight) supported by six or seven others that are not above four foot high, and these are set in a circle, some on end, and some edge-wise, or sidelong, to bear the great one up. They are all of them of the lapis molaris<343> kind, which is the natural stone of the mountain. The great one is much diminished of what it has been in bulk, as having five tuns or more (by report) broke off it to make mill-stones; so that I guess the stone originally to have been between 25 and 30 tuns in weight. The carriage, rearing, and placing of this massy rock, is plainly an effect of human industry and art; but the pulleys and levers, the force and skill by which 'twas done, are not so easily imagined. The common people call it Arthur's Stone, by a lift of vulgar imagination, attributing to that hero an extravagant size and strength. Under it is a well, which (as the neighbourhood tell me) has a flux and reflux with the sea; of the truth whereof I cannot as yet satisfy you, &c. There are divers monuments of this kind in Wales, some of which we shall take notice of in other counties. In Anglesey (where there are many of them) as also in some other places, they are called krom-lecheu; a name derived from krwm, which signifies crooked or inclining; and llech a flat stone: but of the name more hereafter. 'Tis generally supposed they were places of burial; but I have not yet learned that ever any bones or urns were found by digging under any of them.

Edward Somerset Lord Herbert of Chepstow, Ragland, and Gower, obtained of K. Charles 1 the title of Earl of Glamorgan, his father the Lord Marquess of Worcester being then alive; the succession of which family may be seen in the additions to Worcestershire.