Camden's Britannia

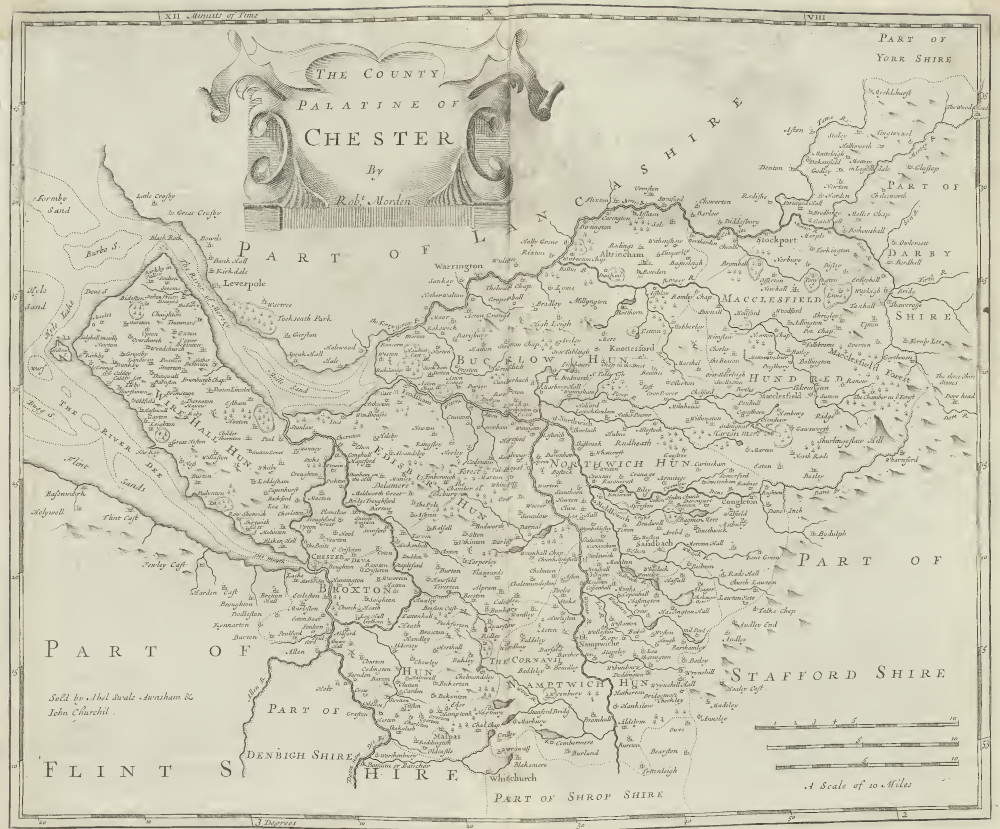

Illustration: Cheshire

(Click here for larger version)

the fifth and last part of these counties formerly possessed by the Cornavii, is the county of Chester, in Saxon Cestre-Scyre, now commonly Cheshire and the county Palatine of Chester; for the Earls of it had a certain palatine jurisdiction belonging to them, and all the inhabitants held of them as in chief, and were under a sovereign allegiance and fealty to them, as they to the King. As for the word palatine (that I may repeat what I have said already of it) it was common to all, formerly, that had any office in the King's court or palace; and in that age comes palatinus was a title of dignity conferred upon him who had before been palatinus, with an authority to hear and determine causes in his own territory; and as well the nobles, whom they called barons, as the vassals, were bound to frequent the palace of the said count, both to give their advice and attendance, and also to grace his court with their presence.

this country, Malmesbury says, yields corn very sparingly, especially wheat, but cattle and fish in abundance. On the contrary, Ranulph of Chester affirms, that whatever Malmesbury might fancy from the report of others, yet it affords great store of all sorts of victuals, corn, flesh, fish, and of the best salmon: it drives a considerable trade, not only by importing but by return, as having within itself, salt-pits, mines, and metals. Give me leave to add further, that the grass of this country has a peculiar good quality, so that they make great store of cheese, more agreeable and better relished than those of any other parts of the kingdom, even when they procure the same dary-women to make them. And therefore, by the by, I cannot but wonder at what Strabo writes, that some of the Britons in his time knew not how to make cheese; and that Pliny should wonder, how barbarous people who lived upon milk, come to despise, or else not know for so long time, the benefit of cheese, especially seeing they had the way of curding it to a pleasant tartness, and of making fat butter of it. From whence it may be inferred that the art of making cheese was taught us by the Romans.

Although this country is inferior to many others of this kingdom in fruitfulness, yet it always produced more gentry than any of them. There was no part of England that formerly supplied the King's army with more nobility, or that could number more knight's families.

On the South side it is bounded with Shropshire, on the East side with Staffordshire and Derbyshire, on the North with Lancashire, and on the West with Denbigh and Flintshires. Toward the North-west it shoots out into a considerable chersonese,<117> the Wirral, where the sea insinuating itself on both sides, makes two creeks, which receive all the rivers of this county. Into that creek more to the West runs the river Deva or Dee which divides this county from Denbighshire. Into that more to the East, the Weaver, which goes through the middle of the county, and the Mersey, which severs it from Lancashire, discharge themselves. And in describing this county, I know no better method, than to follow the course of these rivers. For all the places of greatest note are situate on the sides of them. But before I enter upon particulars, I will first premise, what Lucian the monk has said in general of it, lest I should be accused hereafter for omitting anything that might conduce to the commendation of the inhabitants; besides, that author is now scarce, and as old almost as the Conquest: but if any man be desirous either fully, or as near as may be, to treat of the manners of the inhabitants, with respect to them that live in other places of the kingdom; they are found to be partly different from the rest, partly better, and in some things but equal. But they seem especially (which is very considerable in points of civility and breeding) to feast in common, are cheerful at meals, liberal in entertainments, hasty, but soon pacified, talkative, averse to slavery, merciful to those in distress, compassionate to the poor, kind to relations, not very industrious, plain and open, moderate in eating, far from designing, bold and forward in borrowing, abounding in woods and pastures, and rich in cattle. They border on one side upon the Welsh, and have such a tincture of their manners and customs by intercourse, that they are not much unlike them. 'Tis also to be observed, that as the county of Chester is shut in, and separated from the rest of England by the wood Lyme, so is it distinguished from all other parts of England by some peculiar immunities: by the grants of the kings, and the excellencies of the earls, they have been wont in assemblies of the people to attend the prince's sword rather than the King's crown, and to try causes of the greatest consequence within themselves with full authority and licence. Chester itself is frequented by the Irish, is neighbour to the Welsh, and plentifully served with provisions by the English: 'tis curiously situated, having gates of an ancient model. It has been exercised with many difficulties, fortified and adorned with a river and a fine prospect, worthy (according to the name) to be called a city, secured and guarded with continual watchings of holy men, and by the mercy of our saviour ever preserved by the aid of the Almighty.

the river Dee, called in Latin Deva, in British Dyffyr Dwy, that is, the water of the Dwy, abounds with salmon, and springs from two fountains in Wales, from which some believe it had its denomination. For dwy signifies two in their language. But others from the nature also and meaning of the word, will have it signify black water; others again God's water, and divine water. Now although a fountain sacred to the gods is called divona in the old Gallic tongue (which Ausonius observes to have been the same with our British,) and although all rivers were by antiquity esteemed divine, and our Britons too paid them divine honours, as Gildas informs us; yet I cannot see why they should attribute divinity to this river Dwy in particular, above all others. We read that the Thessalians gave divine honours to the river Paeneus upon the account of its pleasantness; the Scythians attributed the same to the Ister for its largeness; and the Germans to the Rhine, because it was their judge in cases of suspicion and jealousy between married persons: but I see no reason, (as I said before) why they should ascribe divinity to this river; unless perhaps it has sometimes changed its course, and might presage victory to the inhabitants when they were at war with one another, as it inclined more to this or that side, when it left its channel; for this is related by Giraldus Cambrensis, who in some measure believed it. Or perhaps they observed, that contrary to the manner of other rivers, it did not overflow with a fall of rain, but yet would swell so extraordinarily when the South wind bore upon it, that it would overflow its banks and the fields about them. Again, it may be, the water here seemed holy to the Christian Britons; for 'tis said, that when they stood drawn up ready to engage the Saxons, they first kissed the earth, and devoutly drank of this river, in memory of the blood of their holy saviour. The Dee (the course whereof from Wales is strong and rapid) has no sooner entered Cheshire, but its force abates, and it runs through Bonium more gently, which in some copies of Antoninus is spelt Bovium; an eminent city in those times, and afterwards a famous monastery. From the choir or quire, it was called by the Britons Bonchor and Bangor, by the Saxons Bancorna-Byrig and Bangor. This place, among many very good men, is said to have produced that greatest and worst of heretics Pelagius, who perverting the nature of God's grace, so long infested the western church with his pernicious doctrine. Hence in Prosper Aquitanus he is called Coluber Britannus:

pestifero vomuit coluber sermone Britannus.

the British adder vented from his poisonous tongue.

which I mention for no other reason, than that it is the interest of all mankind to have notice of such infections. In the monastery (Bede says) there were so many monks, that when they were divided into seven parts, having each their distinct ruler appointed them, everyone of these particular societies consisted of three hundred men at least, who all lived by the labour of their own hands. Edilfred King of the Northumbrians slew twelve hundred of them, for praying for the Britons their fellow Christians, against the Saxon infidels.

And here, to digress a little upon the mention of these monks' life. The original of a monastic life in the world proceeded from the rigorous and fiery persecutions of the Christian religion; to avoid which, good men withdrew themselves, and retired into the deserts of Egypt, to the end they might safely and freely exercise their profession; and not with a design to involve themselves in misery rather than be made miserable by others, as the heathens pretended. There they dispersed themselves among the mountains and woods, living first solitarily in caves and cells, from whence they were called by the Greeks monachi: afterwards they began, as nature itself prompted them, to live sociably together, finding that more agreeable, and better than like wild beasts to skulk up and down in deserts. Then their whole business was to pray, and to supply their own wants with their own labour, giving the over-plus to the poor, and tying themselves by vows to poverty, obedience, and chastity. Athanasius first introduced this monastic way of living in the western church. Whereunto St. Austin in Africa, St. Martin in France, and Congell (as 'tis said) in Britain and Ireland, very much contributed by settling it among the clergy. Upon which, it is incredible how they grew and spread abroad in the world, how many great religious houses were prepared to entertain them, which from their way of living in common were called Coenobia; as they were also called monasteries, because they still retained a show of a solitary life: and there was nothing esteemed in those times so strictly religious. For they were not only serviceable to themselves, but beneficial to all mankind, both by their prayers and intercessions with God, and also by their good example, their learning, labour, and industry. But as the times corrupted, so this holy zeal of theirs began to cool: rebus cessere secundis, as the poet says; prosperity debauched them. But now to return.

from henceforward this monastery went to decay; for William of Malmesbury, who lived not long after the Norman Conquest, says, there remained here so many signs of antiquity, so many ruinous churches, so many turns and passages through gates, such heaps of rubbish, as were hardly elsewhere to be met with. But now there is not the least appearance of a city or monastery; the names only of two gates remain, Port Hoghan, and Port Cleis, which stand at a mile's distance: between them Roman coins have been often found. But here I must note that Bonium is not reckoned within this county, but in Flintshire, a part of which is in a manner severed from the rest, and lies here between Cheshire and Shropshire.

after the river Dee has entered this county, it runs by the town Malpas or Malopassus, situate upon a high hill not far from it, which had formerly a castle; and from the ill, narrow, steep, rugged way to it, was called in Latin Mala Platea, or Ill Street; for the same reason, by the Normans Mal-Pas, and by the English in the same sense Depen-Bache. Hugh Earl of Chester gave the barony of this place to Robert FitzHugh. In the reign of Henry the Second, William Patrick, the son of William Patrick, held the same; of which race was Robert Patrick who forfeited it by outlawry. Some years after, David of Malpas, by a writ of recognisance, got a moiety of that town, which then belonged to Gilbert Clerk; but a great part of the barony descended afterwards to those Suttons that are Barons of Dudley; and a parcel thereof likewise fell to Urian de St. Petro, commonly Sampier. And from Philip, a younger son of David of Malpas, is descended that famous and knightly family of the Egertons, who derived this name from their place of habitation, as divers of this family have done, viz. Cotgrave, Overton, Codington, and Golborn.

But before I leave this place, I must beg leave in this serious and grave subject, to recite one pleasant story concerning the name of it, out of Giraldus Cambrensis. It happened (says he) in our times, that a certain Jew travelling towards Shrewsbury, with the Archdeacon of this place, whose name was Peche, that is, sin, and the Dean, who was called Devil; and hearing the Archdeacon say, that his archdeaconry began at a place called Ill Street, and reached as far as Malpas towards Chester: the Jew knowing both their names, told them very pleasantly, be found it would be a miracle if ever he got safe out of this county; and his reason was, because Sin was the Archdeacon, and the Devil was the Dean; and moreover, because the entry into the arch-deaconry was Ill Street, and the going forth again Malpas.

From hence Dee is carried down by Shocklach, where was formerly a castle; then by Aldford, belonging formerly to the Arderns; next by Pulford, where in Henry the Third's reign, Ralph de Ormesby had his castle; lastly by Eaton, the seat of that famous family the Grosvenors, i.e. Grandis venator [great hunter].

a little more upward upon the same river, not far from the mouth itself (which Ptolemy calls Seteia, for Deia) stands that noble city, which the same Ptolemy writes Deunana, and Antoninus Deva, from the river; the Britons, Caer-Legion, Caerleon-Vaur, Caerleon Ar Dufyr Dwy, and by way of pre-eminence Caer; as our ancestors the Saxons, Legeacester, from the legion's camp there, and we more contractly, West-Chester, from its westwardly situation; and simply Chester, according to that verse,

cestria de castris nomen quasi castria sumpsit.

Chester from Caster (or the camp) was named.

and without question these names were derived from the twentieth legion, called Victrix. For in the second consulship of Galba Emperor with Titus Vinius, that legion was transported into Britain; where growing too heady and too formidable to the lieutenants, as well to those of consular dignity, as those who had been only praetors; Vespasian Emperor made Julius Agricola lieutenant over them, and they were at last seated in this city, (which I believe had not been then long built) for a check and barrier to the Ordovices. Though I know some do aver it to be older than the moon, to have been built many thousands of years ago by the giant Leon Vaur. But these are young antiquaries, and the name itself may convince them of the greatness of this error. For they cannot deny, but that Leon Vaur in British signifies a great legion; and whether it is more natural to derive the name of this city from a great legion, or from the giant Leon, let the world judge: considering that in Hispania Tarraconensis we find a territory called Leon from the seventh Legio Germanica; and that the twentieth legion, called Britannica, Valens Victrix, and falsely by some Valeria Victrix, was quartered in this city, as Ptolemy, Antoninus, and the coins of Septimius Geta testify. By the coins last mentioned it appears also that Chester was a colony. For the reverse of them is inscribed COL. DIVANA LEG. XX. VICTRIX. And though at this day there remain here few memorials of the Roman magnificence, besides some pavements of chequer-works; yet in the last age it afforded many, as Ranulph, a monk of this city, tells us in his Polychronicon. There are ways here under ground wonderfully arched with stonework, vaulted dining-rooms, huge stones engraven with the names of the ancients, and sometimes coins digged up with the inscriptions of Julius Caesar and other famous men. Likewise Roger of Chester in his Polycraticon, when I beheld the foundation of vast buildings up and down in the streets, it seemed rather the effect of the Roman strength, and the work of giants, than of the British industry.

The city is of a square form, surrounded with a wall two miles in compass, and contains eleven parish churches . Upon a rising ground near the river, stands the castle, built by the Earl of this place, wherein the courts Palatine and the assizes were held twice a year. The buildings are neat, and there are piazzas on both sides along the chief street . The city has not been equally prosperous at all times: first it was demolished by Egfrid the Northumbrian, then by the Danes; but repaired by Aedelfleda, Governess of the Mercians, and soon after saw King Edgar gloriously triumphing over the British princes. For being seated in a triumphal barge at the fore-deck, Kinnadius King of Scotland, Malcolm King of Cumberland, Macon King of Man and of the islands, with all the princes of Wales, brought to do him homage, like bargemen, rowed him up the river Dee, to the great joy of the spectators. Afterwards, about the year 1094, when (as one says) by a pious kind of contest the fabrics of cathedrals and other churches began to be more decent and stately, and the Christian world began to raise itself from the old dejected state and sordidness to the decency and splendour of white vestments, Hugh the first of Norman blood that was Earl of Chester, repaired the church which Leofric had formerly founded here in honour of the virgin Saint Werburga, and by the advice of Anselm, whom he had invited out of Normandy, granted the same unto the monks. Now, the town is famous for the tomb of Henry the Fourth, Emperor of Germany, who is said to have abdicated his empire, and become an hermit here; and also for its being an episcopal see. This see was immediately after the Conquest translated from Lichfield hither, by Peter Bishop of Lichfield; after, it was transferred to Coventry, and from thence into the ancient seat again: so that Chester continued without this dignity, till the last age, when King Henry the Eighth displaced the monks, instituted prebends, and raised it again to a bishop's see, to contain within its jurisdiction this county, Lancashire, Richmond, &c. And to be itself contained within the province of York.

But now let us come to points of higher antiquity. When the cathedral here was built, the earls, who were then Normans, fortified the town with a wall and castle. For as the bishop held of the King that which belonged to his bishopric, (these are the very words of Domesday Book made by William the Conqueror,) so the earls, with their men, held of the King wholly all the rest of the city. It paid gelt<125> for fifty hides,<78> and there were 431 houses geldable, and 7 mint-masters. When the King came in person here, every carucate paid him 200 hestha's, one cuna of ale, and one rusca of butter.<322> And in the same place; for the repairing the city-wall and bridge, the provost gave warning by edict, that out of every hide of the county one man should come; and whosoever sent not his man, he was amerced<295> 40 shillings to the King and Earl. If I should particularly relate the skirmishes here between the Welsh and English in the beginning of the Norman times, the many inroads and excursions, the frequent firings of the suburbs of Handbridge beyond the bridge (whereupon the Welshmen call it Treboeth, that is, the burnt town,) and tell you of the long wall made there of Welshmen's skulls; I should seem to forget myself, and run too far into the business of an historian.

From that time the town of Chester hath very much flourished; and K. Hen. 7 incorporated it into a distinct county. Nor is there now any requisite wanting to make it a flourishing city; only the sea indeed is not so favourable, as it has been, to some few mills that were formerly situated upon the river Dee; for it has gradually withdrawn itself, so that the town has lost the benefit of them, and the advantage of a harbour, which it enjoyed heretofore. Its situation, in longitude, is 20 degrees and 23 minutes; in latitude, 53 degrees, 11 minutes. Whoever desires to know more of this city, may read this passage taken out of Lucian the monk, who lived almost five hundred years ago. First it is to be considered, that the city of Chester is a place very pleasantly situated; and being in the West parts of Britain, stood very convenient to receive the Roman legions that were transported hither: and besides, it was proper for watching the frontiers of the empire, and was a perfect key to Ireland. For being opposite to the North parts of Ireland, it opened a passage thither for ships and mariners continually in motion to and again. Besides, it lies curiously, not only for prospect, towards Rome and the empire, but the whole world: a spectacle exposed to the eye of all the world: so that from hence may be discerned the great actions of the world, and the first springs and consequents of them, the persons who, the places where, and the times when they were transacted. We may also take example from the ill conduct of them, to discern the base and mean things, and learn to avoid them. The city has four gates answering the four winds; on the East side it has a prospect towards India, on the West towards Ireland, and on the North towards the greater Norway; and lastly, on the South, to that little corner wherein God's vengeance has confined the Britons, for their civil wars and dissensions, which heretofore changed the name of Britain into England: and how they live to this day, their neighbours know to their sorrow. Moreover, God has blessed and enriched Chester with a river, running pleasantly and full of fish, by the city walls; and on the South side with a harbour to ships coming from Gascony, Spain, Ireland, and Germany; who by Christ's assistance, and by the labour and conduct of the mariners, repair hither and supply them with all sorts of commodities; so that being comforted by the grace of God in all things, we drink wine very plentifully; for those countries have abundance of vineyards. Moreover, the open sea ceases not to visit us every day with a tide; which, according as the broad shelves of sand are open or shut by tides and ebbs continually, is wont more or less to change or send one thing or other, and by reciprocal ebb and flow, either to bring in or carry out.

from the city, northwestward, there runneth out a chersonese<117> into the sea, enclosed on one side with the estuary Dee, and on the other with the river Mersey; we call it Wirral, the Welsh (because it is a corner) Kill-Gury: this was all heretofore a desolate forest and not inhabited (as the natives say;) but King Edw. 3 disforested it. Now it is well furnished with towns, which are more favoured by the sea than by the soil; for the land affords them very little corn, but the water a great many fish. In the entry into it on the South side, by the estuary, stands Shotwick, a castle of the kings: on the North stands Hooton, a manor which in Richard 2's time fell to the Stanleys, who derive themselves from one Alan Sylvestris, upon whom Ranulph, the first of that name Earl of Chester, conferred the Bailiwick of the Forest of Wirral by the delivery of a horn. Just by this stands Poole, from whence the lords of that place (who have lived very honourably and in a flourishing condition this long time) took their name. Near this is Stanlow, that is, as the monks there have explained it, a stony hill; where John Lacy, Constable of Chester, built a little monastery, which, by reason of inundations, was forced afterwards to be removed to Whalley in the county of Lancaster. At the farthest end of this chersonese,<117> there lies a little barren dry sandy island, called Hilbre, which had formerly a small cell of monks. More inward, East of this chersonese, lies the famous forest, called the Forest of Delamere, the foresters whereof, by inheritance, are the Dones of Utkinton, of an honourable family, being descended from Ranulph of Kingsley, to whom Ranulph the first Earl of Chester gave the inheritance of that office of Forester. In this forest Aedelfleda the famous Mercian lady, built a little city called Eadesburg, that is, a happy town, which has now lost both its name and being; for at present 'tis only a heap of rubbish, which they call the chamber in the forest. About a mile or two from it, are also to be seen the ruins of Finborough, another town built by the same lady.

through the upper part of this forest lies the course of the river Weaver, which issues out of a lake in the South side of the county, at a place called Ridley, the seat of the famous and ancient family of the Egertons, a branch of the barons of Malpas (as I have already observed;) and not far from Bunbury , where is an ancient college built by them; and near to Beeston Castle, a place well guarded both by the mountains, the vast extent of the walls, and the great number of its towers, with a steep access to it. This castle was built by Ranulph the last Earl of Chester of that name: whereof Leland writes thus,

assyrio rediens victor Ranulphus ab orbe,

hoc posuit castrum, terrorem gentibus olim

vicinis, patriaeque suae memorabile vallum.

nunc licet indignas patiatur fracta ruinas,

tempus erit quando rursus caput exeret altum,

vatibus antiquis si fas mihi credere vati.

Ranulph returning from the Syrian land,

this castle raised, his country to defend,

the borderers to fright and to command.

Though ruined now the stately fabric lies,

yet with new glories it again shall rise,

if I a prophet may believe old prophecies.

hence the Weaver continues his course southward, not far from Woodhey, where the famous and knightly family of the Wilburhams lived long in great reputation; also by Bulkeley and Cholmondley, which gave names to two famous and knightly families; and lastly, not far, on one hand from Baddeley, formerly the seat of the ancient family of the Praers; nor on the other hand, from Combermere, in which William Malbank founded a little religious house. When this river touches the South part of this county, it passes through heaths and low places, where (as in other parts of this county) they often dig up trees, which they suppose have lain there ever since the deluge. Afterwards, as it passeth through fruitful fields, it receives a little river from the eastward, upon which is situated Wybunbury, so called from Wibba King of the Mercians. Next to that is Hatherton, formerly the seat of the Orbys, after that of the Corbets, and at present of Thomas Smith, son of Sir Laurence Smythe knight: then Doddington, the estate of the Delvesys: Batherton, of the Griffins: and Shavington of the Wodenoths (who by their name seem to have sprung from the Saxons:) besides the seats of many other honourable families, which are very numerous in this county. From hence the river Weaver goes on by Nantwich, at some distance from Middlewich, to Northwich. These are the noble salt-wiches, about 5 or 6 miles distant one from another, where they draw brine or salt-water out of pits, and do not, according to the method of the old Gauls and Germans, pour it upon burning wood, but boil it upon the fire, to make salt of. Nor do I question but these were known to the Romans, and that their impost for salt was laid on them. For there was a noble way from Middlewich to Northwich, which is raised so high with gravel, that one may easily discern it to be Roman; especially if he considers that gravel is scarce in this county, and that private men are even forced to rob the road of it for their own uses. Matthew Paris says, these salt-pits were stoped by Hen. 3 when he wasted this county; that the Welsh, who were then in rebellion, might have no supplies from them. But upon the next return of peace, they were opened again.

Nantwich, the first of them that is visited by the Weaver, is the greatest and best-built town of this county, called by the Welsh Hellath Wen, that is, White-Salt-Wich, because the whitest salt is made here; by the Latins, Vicus Malbanus, probably from William called Malbedeng and Malbanc, who had it given him upon the Norman Conquest. There is but one salt-pit (they call it the brine-pit) distant about 14 foot from the river. From this brine-pit they convey salt-water by wooden troughs into the houses adjoining, where there stand ready little barrels fixed in the ground, which they fill with that water; and at the notice of a bell, they presently make a fire under their leads, whereof they have six in every house for boiling the water. These are attended by certain women called wallers, who with little wooden rakes draw the salt out of the bottom of them and put it in baskets; out of which the liquor runs, but the salt remains and settles . There is but one church in this town, a neat fabric, belonging heretofore (as I have heard) to the monastery of Combermere. Hence the Weaver runs in a very oblique course, and is joined by a little river which rises in the East, and passes by Crewe, where formerly lived a famous family of that name. At some further distance from the West side of it, stands Calveley, which has given both a seat and name to that noble family the Calveleys; of whom, in Richard 2's time, was Sir Hugh de Calveley, who had the reputation of so great a soldier, in France, that nothing was held impregnable to his valour and conduct. Hence the river goes on by Minshull, the seat of the Minshulls; and by Vale Royal, an abbey founded in a pleasant valley by King Edward the First, where now the famous family of the Holcrofts dwell; then by Northwich, in British Hellath Du, signifying the black salt-pit; where there is a deep and plentiful brine-pit, with stairs about it, by which, when they have drawn the water in their leather buckets, they ascend half naked to the troughs, and fill them; from whence it is conveyed to the wich-houses, that are furnished with great piles of wood. Here the Weaver receives the Dane, which we will now follow.

this Dane, or Davan, springs from the mountains, which separate this county from Staffordshire; and runs without any increase by Condate, a town mentioned in Antoninus, and now corruptly named Congleton, the middle whereof is watered by the little brook Howty, the East side by the Daning-Schow, and the North by the Dane itself. Although this town for greatness, resort, and commerce, has deserved a mayor and six aldermen to govern it, yet it has only one chapel in it, and that entirely of wood, unless it be the choir and a little tower. The mother-church to which it belongs is Astbury, about two miles off, which is indeed a curious thing; and though the church be very high, yet the West porch is equal to it: there is also a spire steeple. In the churchyard there are two grave-stones, having the portraiture of knights upon them, and in shields two bars. Being without their colours, 'tis hardly to be determined whether they belonged to the Breretons, the Mainwarings, or the Venables, which are the best families hereabouts, and bear such bars in their arms, but with different colours.

next it arrives at Davenport, commonly Danport, which gives name to the famous family of the Davenports: and Holmes-chapel, well known to travellers; where, within the memory of this age, J. Needham built a bridge. Not far from this stands Rudheath, formerly an asylum or sanctuary to those of this country, and others, that had broken the laws; where they were protected a year and a day. Next, it runs by Kinderton, the ancient seat of that old family the Venables, who from the time of the Conquest have flourished here, and are commonly called Barons of Kinderton. Below this place towards the South, the River Dane is joined by the Croco, a brook rising out of the lake Bagmere, which runs by Brereton. As this town has given name to the famous, ancient, numerous, and knightly family of the Breretons, so Sir William Brereton has honoured it by raising very stately buildings therein. Here is one thing incredibly strange, but attested, as I myself have heard, by many persons, and commonly believed. Before any heir of this family dies, there are seen in a lake adjoining the bodies of trees swimming upon the water for several days together; not much different from what Leonardus Vairus relates upon the authority of Cardinal Granvellan; That near the abbey of St. Maurice in Burgundy there is a fish-pond, into which a number of fishes are put equal to the number of the monks of that place. And if anyone of them happen to be sick, there is a fish seen floating upon the water sick too; and in case the fit of sickness prove fatal to the monk, the fish foretells it by its own death some days before. As to these things, I have nothing to say to them; for I pretend not to such mysterious knowledge: but if they are true, they must be done either by those blessed spirits whom God has appointed guardians and keepers of us, or else by the arts of the Devil, whom God permits now and then to exert his power in this world. For both of them are intelligent beings, and will not produce such preternatural things, but upon design, and to attain some end or other: those ever pursuing the good and safety of mankind; these ever attempting to delude us, to vex us, or to ruin us. But this is foreign to my purpose.

a little after Croco is got beyond Brereton, it comes to Middlewich, situated near its union with the Dane; where there are two fountains of salt-water (separated from one another by a little brook) which they call sheaths. The one of them is not opened, but at set times; to prevent stealing away the water, which is of a more peculiar virtue and excellence than the other. Whence the Dane runs by Bostock, formerly Botestock, the ancient seat of the noble and knightly family of the Bostocks, which by marriage with Anne the only daughter of Ralph, son and heir of Sir Adam de Bostock Kt. went together with a vast estate, to John Savage. Out of this ancient house of the Bostocks, as out of a fruitful stock, has sprung a numerous race of the same name, which have spread themselves in Cheshire, Shropshire, Berkshire, and other places. Beneath Northwich the Dane unites itself with the Weaver, and then runs on to the West in a straight line, and receives from the East, Peover, that gives its name to the town Peover, by which it passes. This is the seat of that noble and ancient family, the Meinilwarrens, now commonly Mainwaring, one of which called Ralph, married the daughter of Hugh kevelioc Earl of Chester, as appears by an old charter now in the hands of Ranulph the heir of this house. The course of the Weaver is next by Winnington, which both gives seat and name to the famous and ancient family of the Winningtons: and then runs at some little distance from Merbury, which derives that name from a pool under it, and gives the same to the famous family of the Marburys. From hence the river runs near Dutton, the estate of that worthy family the Duttons, descended from one Hudardus, who was related to the Earls of Chester. This family by an old custom, hath a particular authority over all pipers, fiddlers, and harpers of this county, ever since one R. Dutton, an active young gentleman of a great spirit, with a rabble of such men, rescued Ranulph the last Earl of Chester, when he was beset by the Welsh, and in danger of being besieged by them. Nor must I forget to take notice of Nether Whitley in these parts, out of which came the Tuschetts or Towchetts, who are barons Audley of Heighley. Now the Weaver flowing between Frodsham, a castle of ancient note, and Clifton, at present called Rocksavage, a new house of the Savages, who by marriage have got a great estate here; runs at last into the estuary of the Mersey, a river which running down between this county and Lancashire, empties itself here; after it has first passed by some inconsiderable towns, and among the rest by Stockport, which formerly had its Baron ; and received the river Bollin, which flows out of the large forest of Macclesfield, wherein stands the town Macclesfield , from whence the forest has its name. Here was a college founded by T. Savage, first, Bishop of London, and then Archbishop of York; in which several of that noble family, the savages, are buried; and also Dunham, which from Hamon de Mascy by the Fittons and Venables came hereditarily to the famous family of Booth. From hence the Mersey goes on to Thelwall before it is much past Knutsford, i.e. Canute's ford, whereof there are two, the upper and the lower; and then Lee, from whence there is a family of the same name, famous not only for its gentle race, but for the number of its branches. As for Thelwall, 'tis now an obscure village, though formerly a large city, founded by King Edward the Elder; and so called, as Florilegus witnesses, from the trunks of trees fixed in the ground, which, instead of a wall, enclosed it. For the Saxons express the trunk of a tree by the word dell, and the Murus by wall, [as we do at this day.] Upon the mouth of this river stands Runcorn, built in the very same age by Ethelfleda , and now likewise reduced to a few cottages. Since I have so often mentioned this Edelfleda, Ethelfleda, or Elfleda, it will not be improper to note, that she was sister to King Edward the Elder, and wife to Ethelred a petty prince of the Mercians; and that after her husband's death she governed eight years in very troublesome times, to her great praise and honour. In Henry of Huntingdon there is this encomium of her:

o Elfleda potens, o terror virgo virorum,

victrix naturae, nomine digna viri.

te, quo splendidior fieres, natura puellam,

te probitas fecit nomen habere viri.

te mutare decet, sed solam, nomina sexus,

tu regina potens, rexque trophaea parans.

jam nec Caesarei tantum meruere triumphi,

Caesare splendidior virgo virago, vale.

victorious Elfled, ever famous maid,

whom weaker men and nature's self obeyed.

nature your softer limbs for ease designed,

but heaven inspired you with a manly mind.

you only, madam, latest times shall sing

a glorious Queen and a triumphant King.

Farewell brave soul! Let Caesar now look down,

and yield thy triumphs greater than his own.

below Runcorn, more within the county, stands the town Halton, where there is a castle which Hugh Lupus Earl of Chester gave to Nigellus, a certain Norman, upon condition, that he should be Constable of Chester; by whose posterity afterwards it came to the house of Lancaster. Nor must I here omit that William, son of this Nigel, founded a monastery at Norton not far from hence, a town now belonging to the Brookes an ancient family. Whether I should place the Cangi here, who are a people of the old Britons; after much enquiry, I cannot really determine , though I have long considered it. Antiquity has so obscured all memorials of them, that there remain not the least footsteps whereby to trace them. So that though Justus Lipsius, that great master of polite learning, takes me for a competent judge of this controversy, I must ingenuously profess my ignorance, and that I would rather recommend this task to anyone else, than assume it to myself. However, if the Ceangi and Cangi may be allowed to be the same, and I don't know why they may not, then 'tis probable that they lived in this county. For while I was reviewing this work, I heard from some credible persons, that there have been twenty pieces of lead dug up on this shore, of a square oblong form, and thus inscribed in the hollow of the upper part.

IMP. DOMIT. AVG. GER. DE CEANG.

but in others;

IMP. VESP. VII. T. IMP. V. COSS.A C

which seems to have been a monument raised upon account of some victory over the Cangi. And this opinion is confirmed by the situation of the place upon the Irish sea: for Tacitus in the twelfth book of his Annals, writes, that in Nero's time Ostorius led an army against the Cangi, by which the fields were wasted, and the spoil everywhere carried off; the enemy not daring to engage, but only at an advantage to attack our rear, and even then they suffered for their attempt. They were now advanced almost as far as that sea towards Ireland, when a mutiny among the Brigantes, brought back the General again. But from the former inscription, it seems they were not subdued before Domitian's time; and consequently, by chronological computation, it must be when Julius Agricola, that excellent soldier, was propraetor here. Moreover, Ptolemy places the Promontorium, on this coast. Neither dare I look in any other part beside this country for the garrison of the Conganii, where, towards the decline of the empire, a band of vigiles with their captain, under the Dux Britanniae, kept watch and ward. But I leave every man to his own judgment.

as for the Earls of Chester; to omit the Saxons who held this earldom barely as an office, and not as an inheritance: William the Conqueror made Hugh, surnamed Lupus, son to the Viscount de Avranches in Normandy, the first hereditary Earl of Chester and Count Palatine; giving unto him and his heirs this whole county to hold as freely by his sword, as he did England by his crown; (these are the very words of the feoffment.) Hereupon the Earl presently substituted these following barons, Nigel (now Niel) Baron of Halton, whose posterity took the name Lacey from the estate of the Laceys, which fell to them, and were Earls of Lincoln: Robert Baron de Mont-Hault, seneschal or steward of the county of Chester; the last of which family dying without children, made Isabel Queen of England, and John de Eltham Earl of Cornwall, his heirs: William de Malbedenge Baron of Malbanc, whose great grand-daughters transferred this inheritance, by their marriages, to the Vernons and Bassets: Richard Vernon, Baron of Shipbrook, whose estate, for want of heirs male, came by the sisters to the Wilburhams, Staffords, and Littleburys: Robert Fitz-Hugh Baron of Malpas, who (as I have observed already) seems to have died without issue: Hammon de Mascy, whose estate descended to the Fittons de Bollin: Gilbert Venables, Baron of Kinderton, whose posterity remain and flourish in a direct line to this present age: N. Baron of Stockport, to whom the Warrens of Poynton (descended from the noble family of the Earls of Warren and Surrey) in right of marriage succeeded. And these are all the barons I could hitherto find belonging to the Earls of Chester. Who (as 'tis set down in an old book) had their free courts for all pleas and suits, except those belonging to the Earl's sword. They were besides to be the Earl's counsel, to attend him, and to frequent his court, for the honour and greater grandeur of it; and (as we find it in an old parchment) they were bound in times of war with the Welsh, to find for every knight's fee one horse and furniture, or two without furniture within the divisions of Cheshire: and that their knights and freeholders should have corslets and habergeons,<323> and defend their own fees with their own bodies.

Hugh the first Earl of Chester, already spoken of, was succeeded by his son Richard, who together with William, only son of Henry the First, with others of the nobility, was cast away between England and Normandy an. 1120. He dying without issue, Ranulph de Meschines was the third in this dignity, being sister's son to Hugh the first Earl. He dying, left a son Ranulph, surnamed de Gernoniis, the fourth Earl of Chester, a stout soldier, who at the siege of Lincoln took King Stephen prisoner. His son Hugh, surnamed Kevelioc, was the fifth Earl, who died an. 1181 leaving his son Ranulph, surnamed de Blundevill the sixth in that dignity, who built Chartley and Beeston Castles, founded the abbey Dieulacres, and died without issue; leaving four sisters to inherit, Maud the wife of David Earl of Huntingdon; Mabel the wife of William d'Aubigny Earl of Arundel; Agnes wife of William de Ferrars Earl of Derby; and lastly, Avis wife of Robert de Quincey. The next Earl of this county was John, surnamed Scotus, the son of Earl David by the eldest sister Maud aforesaid. He dying likewise without issue, King Henry the Third, bribed with the prospect of so fair an inheritance, annexed it to the crown, allowing the sisters of John other revenues for their fortunes; not being willing (as he was wont to say) that such a vast estate should be parcelled among distaffs. The kings themselves, when this county devolved upon them, maintained their ancient Palatine prerogatives, and held their courts (as the kings of France did in the counties of Champagne) that the honour of the palatinate might not be extinguished by disuse. An honour which afterwards was conferred upon the eldest sons of the kings of England; and first granted to Edward the son of Henry the Third, who being taken prisoner by the barons, parted with it as ransom for his liberty to Simon de Montfort Earl of Leicester; who being cut off soon after, it quickly returned to the crown, and Edward the Second made his eldest son Earl of Chester and Flint, and under these titles summoned him, when but a child, to parliament. Afterwards Richard the Second by Act of Parliament raised this earldom to a principality, and annexed to it the castle of Leon, with the territories of Bromfield and Yale, and likewise the castle of Chirk, with Chirkland, and the castle of Oswalds Street with the hundred, and eleven towns appertaining to the said castle, with the castles of Isabella and Delaley, and other large possessions, which by the outlawry of Richard Earl of Arundel, were then forfeited to the crown. Richard himself was styled Princeps Cestriae, Prince of Chester, but this title was but of small duration, no longer than till Henry the Fourth repealed the laws of the said parliament; for then it became a county Palatine again, and retains that prerogative to this day, which is administered by a chamberlain , a judge special , two barons of the exchequer, three serjeants at law, a sheriff, an attorney, an escheator ,<231> &c.

we have now surveyed the country of the Cornavii, who together with the Coritani, Dobuni, and Catuellani, made one entire kingdom in the Saxon heptarchy, then called by them Myrcna-Ric, and Mearc-Lond, but rendered by the Latins Mercia; from a Saxon word Mearc, which signifies limit; for the other kingdoms bordered upon this. This was by far the largest kingdom of them all, begun by Crida the Saxon about the year 586, and enlarged on all hands by Penda; and a little after, under Peada, converted to Christianity. But after a duration of 250 years, it was too late subjected to the dominion of the West Saxons, when it had long endured all the outrage and misery that the Danish wars could inflict upon it.

this county has about 68 parishes.

additions to Cheshire.

as the county of Chester exceeds most others in the antiquity and royalty of its jurisdiction, and multitude of its ancient gentry; so the famous colony settled in it under the Roman government, has rendered it very considerable for antiquities. Nor had that subject wanted a due examination, or the remains of antiquity lain so long undiscovered, if most of its historians had not been led away with a chain of groundless stories and extravagant conjectures. 'Tis true, Sir Peter Leicester has made due searches into the records relating to this county, especially to Bucklow Hundred, and reported them with great exactness and fidelity; but the Roman affairs he has left so entirely untouched, that 'tis plain he either industriously declined them as foreign to his business, or wanted experience to carry him through that part of history. In like manner, Sir John Doddridge, a man of great learning, in his treatise concerning this county, hath exactly stated the ancient and present revenues thereof; but was not so diligent in his enquiries concerning the original of the County Palatine, as might from a man of his profession have been reasonably expected. However, his defect in this point is in a great measure supplied by what the learned Mr. Harrington has left upon that subject, a gentleman by whose death learning in general, and particularly the antiquities of this county, which he had designed to illustrate and improve, have suffered very much.

to begin then with Mr. Camden, who first observes that this is a County Palatine. It may be worth our notice, that it had this additional title upon the coming over of the Normans. At first indeed William the Conqueror gave this province to Gherbord a nobleman of Flanders, who had only the same title and power as the officiary earls amongst the Saxons had enjoyed; the inheritance, the earldom and grandeur of the tenure being not yet settled. Afterwards Hugh Lupus, son of the Viscount of Avranches, a nephew of William the Conqueror by his sister, received this earldom from the Conqueror under the greatest and most honourable tenure that ever was granted to a subject; totum hunc dedit comitatum tenendum sibi & haeredibus suis, ita libere ad gladium sicut ipse rex tenebat angliae coronam.<324>

the vast extent of the powers conveyed in this grant, carried in them Palatine jurisdiction; though it is certain that neither Hugh Lupus, nor any of his successors, were in the grant itself, or any ancient records, styled Comites Palatini.

as to the original of palatinates in general, it is clear that anciently, in the decline of the Roman Empire, they, as the name imports, were only officers of the courts of princes. The term, in process of time, was restrained to those who had the final determination of causes under the King or Emperor. And those that exercised this sovereignty of jurisdiction in any precinct or province, were called Comites Palatini; and the place where the jurisdiction was used palatinatus, a palatinate. Instances of such personal offices in the court, we may still observe in the Palatine of Hungary; and examples of such local authority we have in the palatinates of the Rhine, Durham, and Lancaster. Whether therefore the ancient Palatines were equal to the praefecti praetorio, the curopalatae, the grand maistres in France, or the ancient Chief Justices in England, we need not dispute, since it is clear, that the Comites Palatini, as all new-erected officers titles, retained many of the powers of the ancient, but still had many characters of difference, as well as some of resemblance.

by virtue of this grant, Chester enjoyed all sovereign jurisdiction within its own precincts, and that in so high a degree, that the ancient earls had parliaments consisting of their own barons and tenants, and were not obliged by the English acts of parliament. These high and unaccountable jurisdictions were thought necessary upon the marches and borders of the kingdom, as investing the governor of the provinces with dictatorial power, and enabling them more effectually to subdue the common enemies of the nation. But when the same power, that was formerly a good bar against invaders, grew formidable to the kings themselves, Henry 8 restrained the sovereignty of the palatinates, and made them not only subordinate to, but dependent on, the crown of England. And yet after that restraining statute, all pleas of lands and tenements, all contracts arising within this county, are, and ought to be, judicially heard and determined within this shire, and not elsewhere: and if any determination be made out of it, it is void, and coram non judice;<325> except in cases of error, foreign-plea, and foreign voucher. And there is no other crime but treason that can draw an inhabitant of this county to a trial elsewhere.

this jurisdiction, though held now in other counties, was most anciently claimed and enjoyed by this county of Chester. The Palatinate of Lancaster, which was the favourite province of the kings of that house, was erected under Edw. 1 and granted by him to Henry, the first Duke of Lancaster; and even in the Act of Parliament that separates that Duchy from the crown of England, King Hen. 4. grants quascunque alias libertates & jura regalia ad comitatum palatinum pertinentia, adeo libere & integre sicut Comes Cestriae infra eundem comitatum Cestriae dignoscitur obtinere.<326> Which ancient reference proves plainly, that the county of Chester was esteemed the most ancient and best settled palatinate in this kingdom. And although the Bishop of Durham doth in ancient plea lay claim to royal jurisdiction in his province a tempore conquestus & antea,<327> yet it is evident that not Durham itself (much less Ely, Hexhamshire, or Pembroke) was erected into a county Palatine before Chester. And as this is the most ancient, so is it the most famous and remarkable palatinate in England: insomuch that a late author, who usually mistakes in English affairs, says of Cheshire, comitatui singulare est quod titulum palatinatus gerat, solis germanis alias notum.<328>

having premised thus much concerning the nature of palatinates, let us enter upon the county itself, wherein the river Dee first leads us to Bangor; famous for the monastery there. But before we go any further, it will be necessary to arm the reader against a mistake in Malmesbury, who confounds this with the episcopal seat in Carnarvonshire called Bangor; whereas (as Mr. Burton observes) the latter was like a colony drawn out of the former. That Gildas, the most ancient of our British writers, was a member of this place, we have the authority of Leland; but upon what grounds he thinks so, is not certain. As for Dinothus, he was undoubtedly Abbot there, and sent for to meet Austin, at the synod which he called here in this island. Whether Pelagius the heretic beionged also to this place (as Camden intimates) is not so certain. Ranulphus Cestrensis tells us, in his time it was thought so by some people, and John of Tynemouth, in the Life of St. Alban, expressly says that he was Abbot here. But this man's relation to the place is not like to derive much honour upon it: the remains of Roman and British antiquity, that have been discovered there by the ploughmen (for now the place is all corn-fields,) are a much greater testimony of its ancient glory. Such are, the bones of monks, and vestures; squared stones, Roman coins, and the like.

from hence the river Dee runs to Chester, the various names whereof are all fetched from the affairs of the Romans; the British from the legion, and the Saxon Ceaster from the fortifications made in that place upon account of the legion being there quartered. That the legion XX was there, is agreed on all hands; but by what name it was called, or when it came over, are points not so certain, but they may admit of some dispute.

for the first, it is generally called Legio Vicesima Victrix, and Camden assents to it; but that seems to be defective, if we may depend upon the authority of an old inscription upon an altar digged up in Chester A.D. 1653. And compared with what Dio has said of this legion. The inscription is this,

I. O. M. TANARO

T. ELVPIVS GALER.

PRAESENS. GWA

PRI·LEG·XXVV.

COMMODO ET

LATERANO

COS.

V. S.L. M.

which I read thus:

'Jovi Optimo Maximo Tanaro

Titus Elupius Galerius

Praesens Gubernator

Principibus Legionis Vicesimae Victricis Valeriae

Commodo & Laterano Consulibus

Votum solvit lubens merito.'<329>

for if that legion was called simply Vicesima Victrix, what occasion was there for doubling the v? To make it Vigesima Quinta, would be a conjecture altogether groundless; and yet if the first v denote Victrix, the second must signify something more. 'Tis true, Mr. Camden never saw this altar, yet another he had seen (which was digged up at Crowdundalwaith in Westmorland) should have obliged him not to be too positive, that those who thought it might be called Valens Victrix, or Valentia Victrix, were necessarily in an error.

VARONIV..... ECTVS

LEG. XX. V. V. &c.

here also we see the v is doubled. Whether the latter signify Valeria, will best appear out of Dio, that great historian, who in his recital of the Roman legions preserved under Augustus, hath these words concerning the 20th legion:. The 20th legion (saith Dio) which is also called Valeria and Victrix, is now in Upper Britain, which Augustus preserved together with the other legion that hath the name of Vicesima, and hath its winter-quarters in Lower Germany, and neither now is, nor then was usually and properly called Valeria.

Mr. Burton is induced by the Westmorland monument to make an addition to Victrix, and sets down Valens; but why this passage should not have induced him rather to make choice of Valeria, I confess I perceive no reason. For first, the distinction he makes between the Vicesima in Britain and that in Germany, is plain not only from the natural construction of the words, but likewise because Dio's 19 legions, which were kept entire by Augustus, cannot otherwise be made up. Next, supposing this distinction, 'tis very evident, that he positively applies the name Valeria to the first, and as plainly denies that the second ever had that title. And why should not we as well allow the name of Valeria to this, as we do to other legions the additional titles of Ulpia, Flavia, Claudia, Trajana, Antoniana?

the second head, when this legion came over, or when they were here settled, cannot be precisely determined. That this was a colony settled by Julius Caesar (as Malmesbury seems to affirm) implies what never anyone dreamt of, that Julius Caesar was in those territories. Giving an account of the name Caerlegion, he lays down this reason of it, quod ibi emeriti legionum Julianarum resedere.<330> The learned Selden would excuse the monk by reading militarium for Julianarum; but that his own ancient manuscript would not allow. To bring him off the other way, by referring Julianarum not to Caesar but Agricola, who in Vespasian's time had the sole charge of the British affairs, seems much more plausible. Before that time, we find this legion mentioned by Tacitus, in Lower Germany; and their boisterous behaviour there. And in Nero's time, the same author acquaints us with their good services in that memorable defeat which Suetonius Paulinus gave to Queen Boadicea. So that whenever they might settle at Chester to repel the incursions of the active Britons; it plainly appears they came over before Galba's time; from the reign of which Emperor, notwithstanding, Mr. Camden dates their landing here.

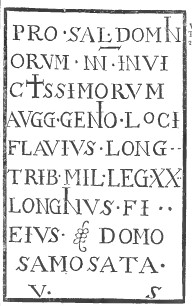

another altar was found at Chester with this inscription.

Illustration: Inscription on an altar found at Chester.

it was discovered by the architect in digging for a cellar in the house of Mr. Heath, and was viewed and delineated by Mr. Henry Prescott, a curious gentleman of that city, to whom we are indebted for the description of it. It lay with the inscription downward upon a stone two foot square, which is supposed to have been the pedestal of it: the foundation lay deep and broad, consisting of many large stones. The earth about it was solid, but of several colours; and some ashes were mixed in it. About the foundation were found signs of a sacrifice, the bones, horns, and heads of several creatures, as the ox, roe-buck, &c., with these two coins:

I. Brass. On the first side, Imp. Caes. Vespasian. Aug. Cos. III. and the face of Emperor. On the reverse, Victoria Augusti S. C. and a winged victory standing.

II. Copper. On the first side, Fl. Val. Constantius Nob. C. and the face of Constantius. On the reverse, Genio Populi Romani, a genius standing, holding a bowl (used in sacrifices) in the right hand, and a cornucopia in the left.

our antiquary tells us, that presently after the Norman Conquest, the episcopal see was translated hither from Lichfield: and this is the reason why the bishops of Lichfield are sometimes called by our historians bishops of Chester; and Peter who translated it, is by our Saxon annals called Episcopus Licifeldensis sive Cestrensis, Bishop of Lichfield or Chester.

leaving this ancient city, the next thing that offers itself is Wirral (called by the Saxon annals Wirheale, and by Matthew Westminster more corruptly Wirhale,) which the same Matthew confounds with Chester, making them one place. This error proceeded from the misunderstanding of that passage in the Saxon Chronicle: Hy gedydon on anre pestre ceastre on wirhealum. Sio is legaceastre gehaten, i.e. They abode in a certain western city in Wirheale, which is called Legaceaster." The latter part of the sentence he imagined had referred to Wirheale, whereas it is plainly a further explication of the western city.

from the western parts of this county, let us pass to the eastern, where upon the River Dane is Congleton, the ancient Condatum of Antoninus, according to our author, Mr. Burton, Mr. Talbot, and others. Wherever it was, it seems probable enough (as Mr. Burton has hinted) that it came from Condate in Gaul, famous for the death of S. Martin. Caesar expressly tells us, that even in his time they translated themselves out of that part of Gaul into Britain; and that after they were settled, they called their respective cities after the name of those, wherein they had been born and bred. Whether any remains of Roman antiquities that have been discovered at Congleton, induced our antiquaries to fix it there, is uncertain, since they are silent in the matter: but if the bare affinity of names be their only ground; supposing the distances would but answer, there might be some reason to remove it into the bishopric of Durham: wherein at Consby near Piercebridge was dug up a Roman altar, very much favouring this conjecture. The draught and inscription of it, with the remarks upon them, shall be inserted in their proper place.

more towards the North lies Macclesfield, where (in a chapel or oratory on the South side of the parochial chapel, and belonging to Peter Leigh of Lyme, Esq. as it anciently belonged to his ancestors) in a brass plate are the verses and following account of two worthy persons of this family.

here lieth the body of Perkin A Legh

that for King Richard the death did die

betrayed for righteousness.

and the bones of Sir Peers his son

that with King Henry the Fifth did wonne

in Paris.

this Perkin served King Edward the Third, and the Black Prince his son in all their wars in France, and was at the battle of Crecy, and had Lyme given him for that service, and after their deaths served King Richard the Second, and left him not in his troubles, but was taken with him, and beheaded at Chester by King Henry the Fourth. And the said Sir Piers his son, served King Henry the Fifth, and was slain at the battle of Agincourt.

in their memory Sir Peter Legh of Lyme knight, descended from them, finding the said old verses written upon a stone in this chapel, did reedify this place an. Dom. 1626.

on the other side of the same parochial chapel, in an oratory belonging to the right honourable Thomas Earl Rivers, is this copy of a pardon graved in a brass plate.

the pardon for saying of v pater nosters and v aves and a... Is xxvi thousand yeres and xxvi dayes of pardon.

another brass plate in the same chapel has this ancient inscription: Orato pro animabus Rogeri Legh & Elizabeth uxoris suae: qui quidem Rogerus obiit iiii. Die Novembris, anno Domini MVCVI. Elizabeth vero obiit v die Octobris, an. Domini MCCCCLXXXIX. Quorum animabus propitietur Deus.<331>

this town of Macclesfield hath given the title of Earl to the Gerrards, the first whereof invested with that honour, was Charles, created Earl of this place, 31 Car. 2, who being lately dead, is now succeeded by his son and heir.

the more rare plant yet observed to grow in Cheshire, is cerasus avium fructu minimo cordiformi Phyt. Brit. The Least Wild Heart Cherry-Tree or Merry-Tree. Near Stockport, and in other places. Mr. Lawson could observe no other difference between this and the common cherry-tree, but only in the figure and smallness of the fruit.